For nearly two years now, the pandemic has dominated just about every corner of multifamily community management—particularly when it comes to indoor air quality, circulation, and filtration. But even before anyone had ever heard of COVID-19, pet dander, pollen, smoke, cleaning and pest control chemicals, mold, and other allergens had the capacity to make life miserable for residents and staff sensitive to such irritants.

When those issues arise in a single-family home, the solution is clear: rehome the cat, remove the plant or bush, kick the habit, and use gentler, more hypoallergenic products for cleaning and exterminating. In a multifamily residential community such as a co-op or condominium, however, eliminating those irritants can be more difficult. The pet may belong to your neighbor; the landscaping choices may not be your domain; and the chemicals used by the exterminator may be out of your control.

But difficult or not, condo and co-op boards have just as much responsibility to address—and ameliorate, if at all possible—residents’ environmental sensitivities as they do a person’s need for a wheelchair ramp or large-print meeting minutes. And these days, with the pandemic dragging on as we head into months of colder temperatures and increased holiday traffic in common areas, keeping the air in your building or HOA as clean as possible has the added benefit of helping to reduce the spread of COVID and other illnesses.

Is Sensitivity a Disability?

According to Ellen Shapiro, an attorney specializing in community law and a partner at the law firm of Marcus Errico Emmer & Brooks, PC, in Braintree, Massachusetts, “Multiple chemical sensitivity in itself is considered a disability. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) administers all these issues. Their position...is that what they refer to as ‘environmental illnesses’ are legitimate conditions. The definition of a disability under HUD—and that’s the definition we use—is a condition that substantially limits a major life activity. HUD rules apply nationwide. States may expand upon them, but not diminish them.”

The legal framework under which we consider disabilities is further defined under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), explains Mark Hakim, of counsel at New York-based law firm Schwartz, Sladkus, Reich, Greenberg & Atlas. “The Americans with Disabilities Act, as amended from time to time, is a federal law protecting those with legal disabilities,” he says. “Under the ADA, a person with a disability is someone who has a physical or mental impairment that seriously limits one or more major life activities, or who is regarded as having such impairments. [It] includes impairment that substantially limits one or more of a person’s major life activities such as breathing, seeing, hearing, walking, sitting, standing, sleeping, caring for yourself, lifting, or learning. It also requires having a record of an impairment and/or being regarded as having an impairment. Asthma and allergies are generally considered disabilities under the ADA. Respiratory and other conditions caused or exacerbated by smoke and chemicals may also constitute a disability under the ADA.”

Lisa Magill, an attorney with Kaye Bender Rembaum in Pompano Beach, points out that the criteria for designating an impairment are “very subjective, as it’s defined by a medical professional of the person seeking redress.” This subjectivity can put a great deal of uncertainty on the co-op or condo association dealing with an issue of environmental sensitivity.

Key among the considerations to be taken into account if a resident is requesting accommodations to address an environment-sensitive health condition is whether or not what they’re asking for can be considered “reasonable” under the law. Sima Kirsch, a community law attorney located in Chicago, Illinois, observes that “although the special accommodation requested must help the owner overcome the limitations that arise when one or more of their significant life functions are impacted, the request will unfortunately not be considered reasonable if the application imposes undue financial burden on the HOA.

“Nevertheless,” she continues, “if there is no impact on the association or others, it would be discriminatory if the HOA refused to allow the owner to perform modifications [or other preventive measures] at that owner’s cost. If modifications are needed for a resident to fully use and enjoy their premises…it’s best for the board to permit [the alterations].”

Smoke

Secondhand cigarette smoke is a known health hazard and has become a major issue in both residential and commercial settings. Smoking is banned in many public and semi-public places by local ordinance, and in the governing documents of many condominium and cooperative communities, smoking is banned in public or common areas. In New York City, for example, a local ordinance was recently enacted requiring all residential buildings—condo, co-op, or rental—to post a property-wide smoking policy. In Massachusetts, according to Shapiro, while smoking is prohibited in common areas in most associations, it is still permitted in individual units.

According to Scott Piekarsky, an attorney and principal at Piekarsky & Associates, located in Wykoff, New Jersey, “If someone is affected in their unit by conduct in another unit, then for good or bad, that problem is the association’s problem.” If a resident is experiencing health effects from someone else’s smoking, “the smoke is obviously traveling through limited common elements—which the association is responsible for,” says Piekarsky, “so they’ve got to address it” or risk costly, acrimonious litigation.

“Furthermore,” says Piekarsky, “in New Jersey condominiums, there’s a state legal requirement that residents be offered alternative dispute resolution (ADR) to resolve conflicts [before litigation is permitted to move forward]. Simply, if there is a dispute between unit owners, or an owner and the association, the association must provide ADR mechanisms to resolve the dispute. Automatically, the association is in the loop.”

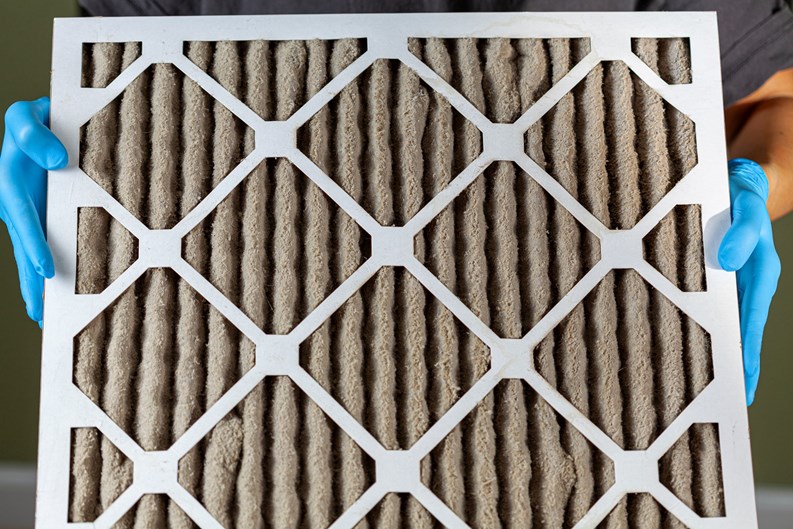

Shapiro points out that resolving the issue of an allergen or other environmental irritant comes down to a matter of who has jurisdiction over the means by which the irritant is being transmitted throughout the building. “It can be a question,” she says, “of whether the association manages the HVAC system—which typically it does. Can they put in filters? [The board’s] best course of action is to take whatever action they can within their power; whatever is beyond the capacity of the association to do must be sent back to the owners involved in the conflict to be worked out between them.”

Pets

For many residents, pets are an important part of their lives, whether it be a dog, cat, or goldfish. For others, neighbors’ animal friends can be the source of much sniffling and teary eyes, or may even aggravate more serious conditions, like asthma or emphysema. Obviously, people with allergies or sensitivities to dander and pet hair can simply opt not to keep animals in their unit—but what about residents with the most severe sensitivities, for whom even a little bit of pet dander or odor wafting into their unit through the HVAC system can be a cause big problems?

Ordering pet owners to give up their furry or feathered family members clearly isn’t an option—at least not in buildings or HOAs whose governing documents allow pets. Speaking of her own state, Magill says, “If you don’t have a restriction in your documents that prohibits pets, then under the Florida State Condominium Law, you have no right to tell anyone to get rid of their pets.” That said, however, “The association does have an obligation to make an accommodation—or even allow a physical alteration to the premises to ameliorate the impact of [an allergic resident’s] disability.”

Co-op vs. Condo

Hakim points out that in New York, where co-op buildings are very common, the circumstances may be a bit different due to the ownership differences between the co-op shareholder, who lives in the building under a proprietary lease, and a condo owner, who is a member of an association and an owner of real property in his/her own right.

“In a co-op, due to the nature of the legal relationship between shareholder and the cooperative corporation, the board of directors has a legal obligation under an implied Warranty of Habitability to ensure that a [resident’s] apartment is safe and livable at all times,” says Hakim. “Irrespective of whether any claimed odor-related illness rises to the level of legal disability (for which the board would have to work towards making reasonable accommodations), the board must ensure that no condition is created or permitted that would breach the complaining shareholder’s Warranty of Habitability.”

In the case of drifting pet dander, for example, Hakim says, “That would include taking measures to ensure that any neighboring cats—including their dander and odor—are not materially and adversely affecting the other occupants of the building. The board will want to investigate the claim and work with the parties to find resolution. In either event, a determination should be made confirming the alleged conditions, that they are the cause [of the complaining residents’ symptoms], and that [those symptoms] rise to the level of disability under the ADA and/or are sufficient to constitute a breach of the Warranty of Habitability or proprietary lease. Under most proprietary leases, a shareholder is not permitted to allow unreasonable odors to escape their apartment, so if odors—caused by cats, for example—are escaping the apartment, it could constitute a breach under the proprietary lease.”

Hakim goes on to say that “in a condominium, where there is no proprietary lease and implied Warranty of Habitability, the association’s obligations—if any—would generally depend on whether the dander and odors are directly related to the cats, and whether the alleged sickness is so severe that it would constitute a disability under the ADA. If so, then the condo’s board of managers would have to work towards finding a reasonable solution—though generally speaking, in the case of both a co-op and condominium, they are not required to demolish, materially change, or build something from scratch. Thus, possible solutions (short of trying to have the offending animals removed) may include adjusting the airflow in an apartment, sealing off gaps, or requiring the adjacent apartment owner to install HEPA or similar air filters.”

Chemicals

Another potential hot-spot is the use of chemicals indoors to control pests, and outdoors to maintain landscaping. Many residents claim the chemicals used adversely affect them, their kids, or their pets. Shapiro points out that in today’s ecologically conscious world, many associations request—and many exterminators use—environmentally friendly chemicals. If a resident has a problem with even those, that resident should be notified in advance that the exterminator is coming, so they can make arrangements for themselves and their family (and their pets, if necessary) to be away from the building until the fumes dissipate—usually just a few hours’ time. “I don’t think we have to fail to protect all the other owners from vermin,” Shapiro says, “because someone’s pet doesn’t like pesticides.”

Mold

In certain situations, it’s obvious that a condominium association or a co-op corporation is obligated to remunerate any damage caused by the growth of mold on their property. In the case of Florida, for example, such situations usually fall under what is known as a “casualty loss”—in other words, the result of a natural disaster like a hurricane. Clearly, the association and its insurer will do everything they can to eliminate mold from the property after a flood or other catastrophic event.

But what about other potential mold problems not caused by a natural disaster? According to Magill, “If one has mold in their unit, it’s their responsibility. If the portion of say, a pipe, that is the cause of the mold is in the association’s common area, it’s the association’s responsibility. That is without regard to liability factors. In Florida, the law has changed so that the association insures the entire building; structure, internal plumbing, windows, doors, A/C units. This enables the association to rebuild after a casualty loss, even if the unit owner decides not to step up and rebuild their apartment interior.” She adds that it’s completely different for an HOA. In an HOA, unless the units are physically connected—think townhouses—“the owners are responsible for everything.”

In the final analysis, says Shapiro, “Be reasonable. If an association can make an accommodation, they should.” As with so many issues in co-op, condo, and HOA living, after the incident, you’re still neighbors and you have to live together and with each other.

A J Sidransky is a staff writer/reporter for CooperatorNews, and a published novelist. He can be reached at alan@yrinc.com.

Leave a Comment