Taking care of a co-op or condo building’s budget and finances is a big job. Handling such large sums of money is an important responsibility, and not every shareholder or unit owner has the expertise to do the job well. Sure, most people know the that the amount of money going out shouldn’t exceed the amount of money coming in, and people with even a small amount of financial experience know the difference between the capital budget and the operating budget.

But it’s much more complicated than that. And because it is so complicated, managing a community's books often becomes a joint effort, involving the board, manager, accountant and others. It’s important to get anyone who has any relevant expertise into the mix—and part of the process is knowing some basic terms and concepts that apply to multifamily communities, whether condo, co-op, or HOA.

First Things First

The major financial indicators are contained in a monthly report provided by the property manager, which is reviewed by the treasurer or other board members each month. “As the duties of the board require monitoring of cash balances, cash flows, and the approval/timing of major repair and replacements, a qualified board should have a good understanding of how to read their financial statements,” says Chip Swinarski, CPA at the accounting firm of Swinarski & Company in Lake Worth. “A qualified board should be skilled at budgeting, and have a cognizance for reviewing variance reports to identify problems, trends and other financial indicators.”

First, let’s look at some of the main components of a typical co-op or condo building’s financial profile. According to Richard Montanye, CPA, a partner at the accounting firm of Marin & Montanye, LLP in Uniondale, New York, these include working capital position, available cash, capital reserves, long-term debt and budget status.

Because a board or building administrators look at a building’s financial statements to see if there is adequate money for projects, there should be a “floor” for reserves. “We use about $2,000 per unit as a minimum reserve fund,” says one financial professional. “You might have $200,000 and a $100,000 reserve fund, but you can’t really spend all that money.”

Much of the needed information can be found in the co-op, condo or HOA development’s financial statements. These include the balance sheet (reporting assets and liabilities); a statement of revenues, expense and accumulated surplus or deficit; the statement of cash flows (a reconciliation of the balance of cash at the beginning of the year to the balance at the end of the year); notes to financial statements and more.

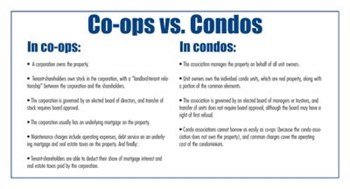

Co-op vs. Condo

There are also important differences between a co-op’s finances and those of a condo or HOA. A good rundown of how things work in each type of development might look something like this.

In co-ops:

• A corporation owns the property.

• Tenant-shareholders own stock in the corporation, with a “landlord-tenant relationship” between the corporation and the shareholders.

• The corporation is governed by an elected board of directors, and transfer of stock requires board approval.

• The corporation usually has an underlying mortgage on the property.

• Maintenance charges include operating expenses, debt service on an underlying mortgage and real estate taxes on the property. And finally:

• Tenant-shareholders are able to deduct their share of mortgage interest and real estate taxes paid by the corporation.

In condos, on the other hand:

• The association manages the property on behalf of all unit owners.

• Unit owners own the individual condo units, which are real property, along with a portion of the common elements.

• The association is governed by an elected board of managers or trustees, and transfer of units does not require board approval, although the board may have a right of first refusal.

• Condo associations cannot borrow as easily as co-ops (because the condo association does not own the property), and common charges cover the operating cost of the condominium.

More Basic Concepts

Let’s delve a little further into the subject. As we’ve mentioned, one important difference is that a co-op may find it easier to get loans because it owns the buildings and the land on which they stand as collateral.

In a condo, on the other hand, its ability to borrow is based on cash flow, according to Carl Cesarano, CPA, a principal with the accounting firm of Cesarano & Khan, P.C., in Floral Park, New York. “In condos,” he says, “getting financing is a whole different ball game. You are budgeting a surplus.”

Whatever type of building you have, there are several basic budgeting concepts that the average board member should understand in order to effectively manage that community’s finances. Again, it can be broken down into several basic points, according to the pros.

• The annual operating budget must be balanced. Operating costs must be covered by maintenance or common charges from owners and other regular sources of income.

• The development should establish a long-term capital budget (5 to 10 years), and should budget for future repairs and replacements.

• Capital budgeting should also include a funding plan (regular assessments, periodic special assessments, earmarking specific sources of revenue such as transfer fees, borrowing, etc.).

Some accountants feel that accrual budgeting is a better system than cash budgeting. In a cash system, the board doesn't see bills unless they've paid them. They also wouldn’t see payments until they are actually received. In an accrual system, on the other hand, income is counted when the sale occurs, even if you haven’t received it yet, and expenses are counted when you receive goods and services, even if you haven’t made a payment yet. In addition to how much you have on hand, an accrual system also includes how much you owe and how much you’re entitled to.

The Budget Process

How does a board begin their budget for the coming fiscal year?

To begin with, they don’t start from scratch. They use the past year’s budget as a starting point. Then, they typically factor in predictions and expected changes, such as changes in real estate taxes (for co-ops), union contracts (which affect the wages paid to building or association staff), fuel costs, changes in assessed value of real estate and changes in water and sewer rates, and insurance premiums, for example.

Expected expenses should also be factored in. Sometimes you know when to expect more repair costs. For example, if your building just underwent an elevator overhaul, the contract likely included several months of maintenance. Once that time expires, any repairs will have to be paid out of pocket.

The fact that repairs will eventually be needed is unavoidable, but when they'll be needed and how much they will cost is hardly an exact science. To reduce at least some of the variables, the typical operating budget worksheet includes all sorts of expenses, both past and projected, are represented: Wages, payroll taxes, employee benefits, real estate taxes, interest expense, pre-payment premium, fuel, utilities, water and sewer, repair and maintenance, supplies, insurance, management fees, professional fees, licenses and permits, state and local franchise taxes and 'other.'

Expertise

Exact science or not, budgeting is a complex undertaking that isn’t for novices. Buildings and HOAs definitely need to have a professional to guide their decisions. In most cases, the management company retains outside accountants who are often consulted for important transactions, such as sale or acquisition of units, funding of capital projects or assessments.

Self-managed buildings typically deal directly with their outside accountant. ‘Self-managed buildings actually need their professional more,” says Montanye, “since they do not have an experienced agent to rely upon.”

The experts note that in addition to hired accountants, buildings often also rely on residents who have relevant experience in a particular field. “He or she doesn’t have to be an accountant,” he says. “They could be a retired school administrator who knows about budgets, buying fuel, repairs.”

For Cesarano, the budgeting and financial process for co-ops and condos works best as a team effort.

“Every co-op and condo should build a team of professionals,” he says. “The budgeting process should start with the manager, then have the team look at it. The accountant should be part of the team—the accountant is also the auditor and he has a lot of expertise. You need the expertise of an engineer. If there’s a tax certiorari attorney, get him on the team. Let your board look at it—they’re the real management. If you have your team in place, then you’ll come up with a good product.”

What are some of the most common mistakes that boards make in terms of budgets? Montanye feels that the most common mistake made is having unrealistic expectations. “Sometimes boards will ignore professional advice and projections in favor of lower maintenance,” he says. “This makes subsequent decisions more difficult, since they first have to make up for a loss and then fund a much larger deficit, which had been ignored previously.”

Common Mistakes

One of the most common mistakes boards make when it comes to budgets is over-reliance on property managers’ internal control structures. They're different at different property management firms, so it's important that the board monitor the property manager, monitor bills over a certain amount and make sure reserves are being used appropriately.

“There have been some high-profile frauds in the industry where the board placed too much reliance on the managing agent, and didn’t monitor them enough,” says one CPA professional. Other common mistakes cited include deferring or avoiding maintenance increases, budgeting a deficit, failing to establish and long-term capital budget, and failing to fund future repairs and replacements that were identified in a long-term capital budget.

To help avoid these and similar problems, professionals recommend that board members keep a close eye on the process, attend meetings, pay attention to details, don’t be afraid to ask questions, and seek the advice of your management company and your professionals (attorneys, accountants, engineers) whenever needed. Also, make sure your operating budget is balanced, remember to establish a long-term capital budget and have a realistic funding plan.

The Info Is Out There

If you need more information on the subject, there’s plenty out there. What resources exist for boards and/or managers to get solid advice on how to better organize and manage their financial records? There are many resources that are available to interested co-op and condo boards and property management companies.

“If they're self-managed, they probably need to consult with either an accountant, or a management company, and decide what to do from there,” says Brad Schneider, president of CondoCPA, which provides audit accounting and tax services for community associations, and has offices in Sarasota, Tampa and Orlando, and locations in Illinois and California.

“They can also have an audit done, and if the issue is with the management company itself, the audit should come up with recommendations on dealing with the books. If they're self-managed and they're having problems with bookkeeping, the two alternatives are 1) to get a full management contract, or 2) at least contract out their accounting.”

Seminars, including those given by trade organizations or at trade shows such as the South Florida CooperatorExpo, are another resource. “In the big picture, the obligations of the board member, and more so of the treasurer don't just stop because the property manager is doing a good job,” says Matthew Zifrony, an attorney and a director at the law firm of Tripp Scott in Fort Lauderdale.

“Here in South Florida we are very fortunate to have a number of professional associations that offer training and education,” says Swinarski, from property management firms to lawyers. And he adds, the state’s Division of Condominiums, Timeshares & Mobile Homes, through the Florida Department of Business & Professional Regulation, also offers educational materials and training for board members.

As we mentioned earlier, the building’s accountant is not always available. But when attending trade shows, board representatives or managers should look at some of the accounting systems or software being offered, and see whether they are more efficient than the systems they are using now.

That's why it pays—literally—to have a competent financial professional on hand to help your community keep a clean fiscal house, and be prepared for both day-to-day expenses, as well as the inevitable surprises.

Raanan Geberer is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The South Florida Cooperator.

Comments

Leave a Comment